Where do ideas come from? How do you know if a story idea is good or not? And is it true that Danish writer/artist Palle Schmidt wrote a big Hollywood movie? Yes! Well, almost…. This video uses music from https://www.bensound.com

how to

Coloring in Photoshop – 5 Steps for the Absolute Beginner

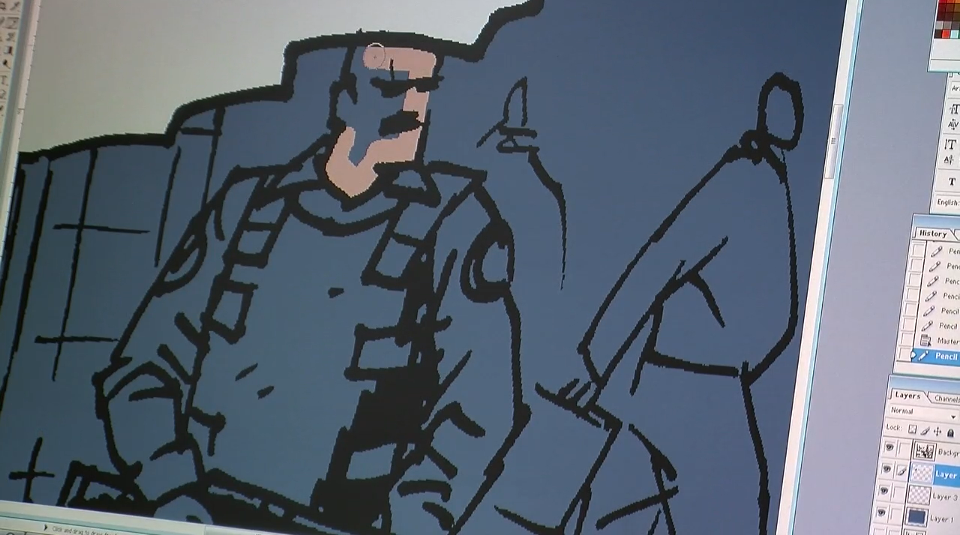

Digital coloring can be just as elaborate and detailed as an oil painting. But if you’re just getting started, here is a simple step-by-step guide for getting ready to color your comics in Photoshop.

Step # 1: Scan your line art.

I would recommend scanning in Grayscale and converting to Bitmap after. The resolution should be at least 300 dpi (dots per inch), maybe even 600 dpi. I would also recommend converting your line art to bitmap before you start working on it, to make sure the lines are crisp and clean.

Step # 2: Grayscale to RGB

I know I just told you to convert your line art to Bitmap – But in order to start coloring, you need to convert it back to grayscale, before you can convert it to RGB.

Step # 3: Copy your background layer

Making a copy of your line art layer is a good precaution, in case you screw something up. Click the visibilty of the original layer off and set the layer mode of the copy to “multiply”. This basically transforms your line art layer to the equivalent of clear plastic film that you put on top of your color layer.

Step # 4: Color layer(s)

Make a new layer in “Normal” mode, and make sure to place it under your line art layer.

Step # 5: Start coloring!

That’s it! No more steps really, unless you want to get creative – which you should! But this post is meant to just get you started, so these 5 steps are all you need to know for now, except this:

Bonus step: Save, flatten, save again.

When you have finished coloring your page (and along the way, just to be sure) save your work as a Photoshop file, so you have a back up including all the layers.

Then go to the “layers” menu and click “flatten image”.

If you intend for your comic to be printed, convert the color mode to CMYK and save it as a Tiff file. If it’s for web use or an inkjet printer, keep it in RGB and save it as a Jpeg.

Related post: Tips for Digital Coloring

Dealing with Tangents in your Art

One of the most important art lessons I ever got was when my studiomate Ole Comoll showed me what tangents are – and how to avoid them.

In this video I try to pass that lesson along while using examples from my own art. Tangents are everywhere – and once you see them, you can’t unseen them. You’ve been warned!

Step-by-Step Guide: My Comics Process

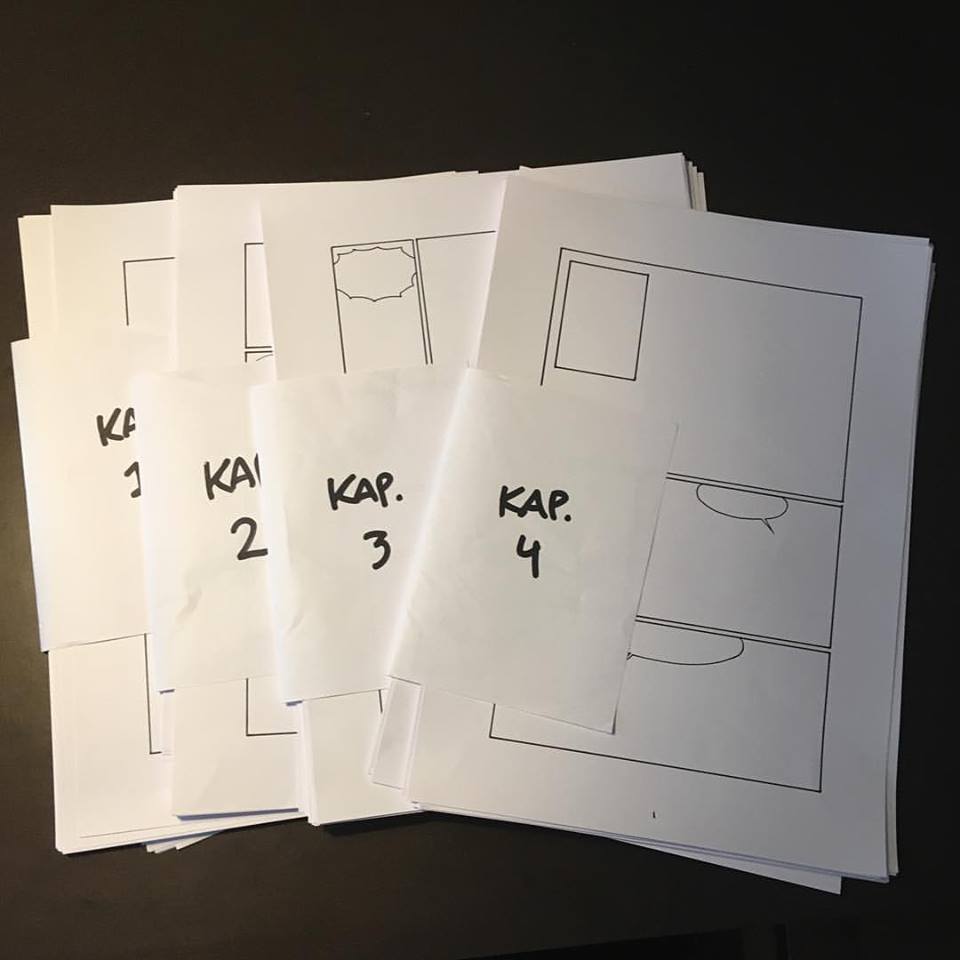

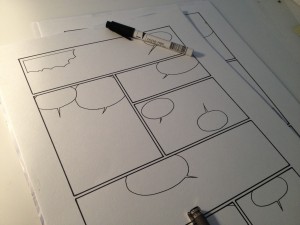

This is my next graphic novel project! Filling in the blanks should be no biggie, right? Well, there’s a little more to it than that.

I recently posted this picture on Instagram and Facebook that got a lot of likes – and a lot of questions! So I thought I’d elaborate a bit on how I actually tackle the creation of a comic or graphic novel. I go into detail with certain elements in my premium 10-video tutorial series, but these are the basic steps I go through every time.

I recently posted this picture on Instagram and Facebook that got a lot of likes – and a lot of questions! So I thought I’d elaborate a bit on how I actually tackle the creation of a comic or graphic novel. I go into detail with certain elements in my premium 10-video tutorial series, but these are the basic steps I go through every time.

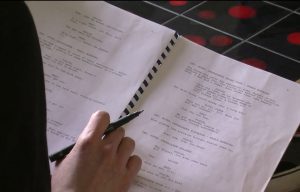

1: Script

1: Script

Having a finished script before you start drawing increases your chance of actually finishing with about 3000 percent. The first 2 videos of the premium series covers this (and those episodes are free). Sometimes I’ll get a script from another writer but I often work off my own or have to break the story down into pages.

2: Thumbnails

This is little scribbles just to get a grip of the page breakdowns. I don’t neccesarily do it for every page but it can be very helpful. The more I plan before I start drawing, the more smoothly the rest of the process. There is a podcast episode about making those hard choices here.

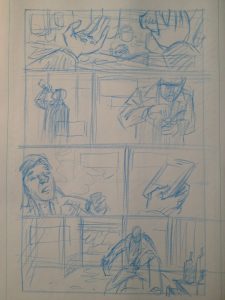

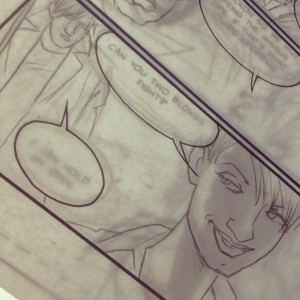

3: Rough sketches

3: Rough sketches

Once I know sort of what the layout of the page will look like, I can start rough sketching pictures. As you’ll notice, this is bare bones storytelling, just enough for others to make out what is going on. No more, no less. I usually sketch on half pages, not full size. No need for bigger format when I’m not doing details – in fact the smaller format often helps in creating a clear layout.

4: Borders and lettering

After scanning my rough sketches, I put them in an InDesign document. If it’s an issue of a comic, I’ll make seperate 22-page files that stick to the same template. I’ll start by creating a standard border for the entire project and just plunk that in between all the frames. Then I’ll put the lettering in where it needs to go. Please note, that this is not the final document! I can adjust the lettering once I have the finished art. For full breakdown of this process go here.

5: Borders and balloons

5: Borders and balloons

Using a print-out of my now lettered rough sketches, I am ready to draw the actual pages. BUT, since I might need my borders and speech balloons in a clean format, I do the boring work of inking that part first. This is what the image I posted on Instagram portrayed – I can see why there was some confusion as to how I actually worked!

After I’ve traced the borders and balloons on the board I intend to do the rest of the artwork on, I scan the whole thing. Why? I’ll explain in step #8.

6: Sketching

Using my rough sketches as a guide, I’ll sketch the pages going into more detail, especially on backgrounds and stuff. A picture might change from my original ideas, but I always stick within the frames I already decided on. There’s a video of that process here.

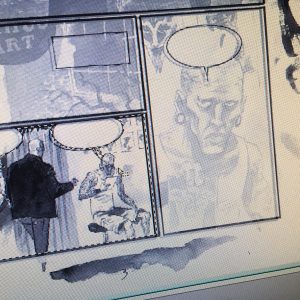

7: Inking

7: Inking

Using a lightbox I trace my skectched pages on the boards that already has the borders and balloons. I can adjust the images a bit if needed. Sometimes I do painted art and other times I ink with black markers. There’s a video of me inking a page of Thomas Alsop here.

I don’t need to worry about paiting outside the borders in this stage because I’ve already scanned the clean pages with just balloons and borders, and no art.

8: Scanning and clean-up.

8: Scanning and clean-up.

Remember when I said I might need the borders clean? This is the step. I used to I scan my inked pages and clean up mistakes where I painted outside the frames or over speech balloons. Now I just use the already scanned borders. I just smack my clean borders over the finished art in Photoshop, turn the opacity down a bit so I can see what I’m doing and adjust the corners. It took me a while to figure this out, because sometimes a scanner will skew things a little bit. But I discovered that if I do a “free transform” and focus on the four outer corners of the borders, the rest will sort itself out.

Once the two layers match up, I’ll select all the white within the frames on the top layer and delete that. Then I turn the opacity of the layer back up to 100% and viola! I now have a layer with nice, clean borders and balloons on top, and whatever mistakes (painting outside the borders) I made are hidden underneath. I flatten the file and export it, usually as a high-res tiff file.

8.1: Coloring (optional)

I’m not gonna go into detail here, but you might want to check out this post on coloring in Photoshop.

9: Repeal and replace!

Admitted, I don’t really call it that. But I do have to go through my already lettered InDesign file and delete all the border blocks and replace my rough sketch with the finished art. Some adjusting to the lettering is usually neccesary but then I have the entire book or issue ready to send to the graphic designer or export as a PDF directly for print.

10: Celebrate

I usually skip this step, honestly. But having typed up this post and seeing how much work goes into creating a graphic novel, I feel like I should make a point of this going forward.

Hopefully this answered some of your questions and gave you a few ideas to implement in your own process. Please share this post if you found it helpful!

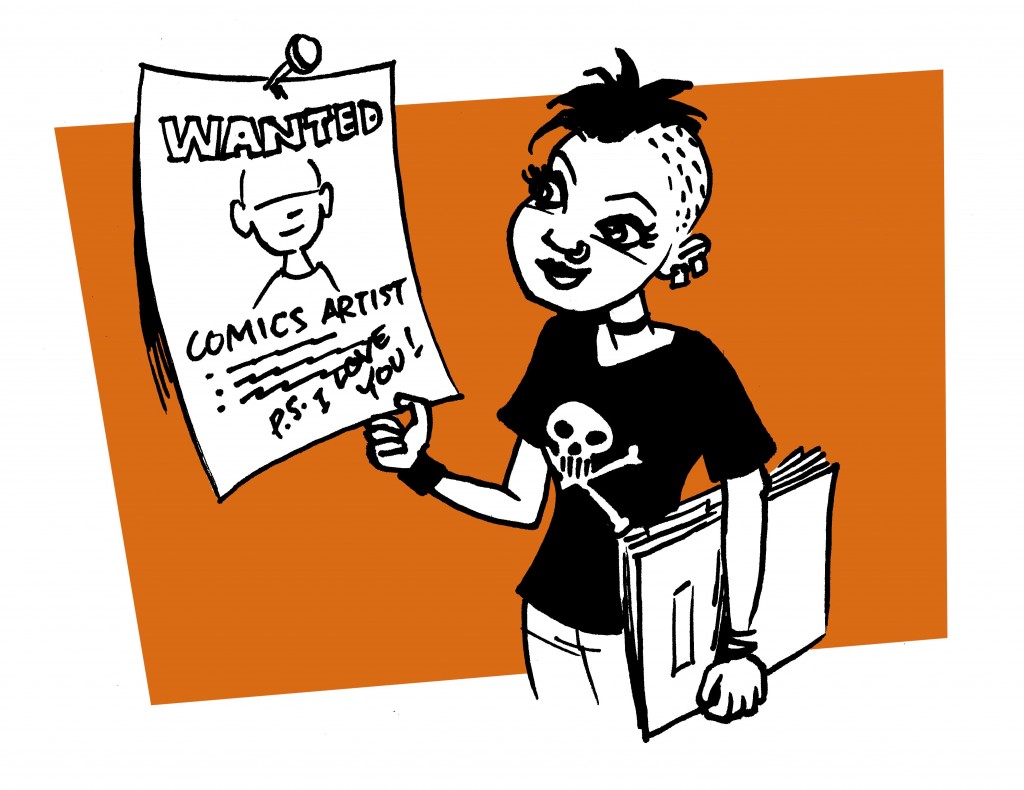

How to Catch an Artist

This blog is focused on comics creation as a whole, rather than seeing writer and artist as two separate things. But what do you do if you have a great story written but don’t feel you have the drawing skills to pull it off?

This blog is focused on comics creation as a whole, rather than seeing writer and artist as two separate things. But what do you do if you have a great story written but don’t feel you have the drawing skills to pull it off?

It’s a big commitment for an artist to draw a comic book that someone else wrote.

Getting an artist on board on your big project is not going to be easy, unless you have the cash to pay for their time. And even then, you’re competing with other commitments and paid work.

Being both a writer and an artist, I can see things from both sides. And I know there are more people out there who can write than there are people who can draw. Time is another important factor. You can write five 22-page issues of something in the same time it takes an artist to draw just one. So how do you lure someone into spending weeks and months hunched over the drawing table working on your book?

Here’s what I think will help:

- A script. I would never agree to draw something from a pitch or an idea. If a writer can’t show me any writing, all the alarm bells go off. And if I am expected to commit to a longer series, I need not only a script for the first ten pages, I need to know where it’s all going. I need to know the writer can write and has a plan.

- A track record. Again, showing that you can produce something helps convince others to get on board. If you have other finished projects on your resume, you may be able to hook an artist with just a detailed outline with a beginning, middle and end. A few pages of script is still necessary, to show that you can write.

- A smaller commitment. It’s much easier to agree to draw ten pages in black and white, than a six issue series or a fully painted graphic novel. As a writer, this also gives you a chance to see how the relationship works out. Just because an artist can show excellent work doesn’t mean they can produce it consistently, keep a schedule or be easy to work with. Doing a shorter story is mutually beneficial.

- Money. Sure, we are all for sale. The more money you can put up front, the harder it is for an artist to say no. But like mentioned above, artists can be flaky, so doing a shorter thing together is a good idea before you pay an artist a huge sum for a book they may never deliver.

- Ownership. If you offer to give the artist a creator credit, it helps sell the message that you are both in the same boat. If you do a pitch together (see this page for how to create a compelling pitch) to get a publisher, having split ownership of the property makes the artist invest more time and effort.

- Trust. The cornerstone to any working relationship is reliability and trust. To get an artist to commit time and energy to your project, you need to trust them to do their thing without you looking over their shoulder. You need to trust their decisions and listen to their input – or at least pretend. But you also need to deliver on your promises and not be late with a script, feedback or payment.

Happy hunting!

PS: Even if you never plan to draw anything, it might be a good idea to at least have an idea of the process. So sign up for my 100% free 7-day crash course here.

Comics for Beginners Podcast Episode 30 – Why We Quit

Making comics is fun – but also hard and lonely work! What do you do when you are dissatisfied with your story or your art? How do you stay motivated, when no one seems to care? How do you stay on track when you meet resistance from within? I offer some personal advice and insights in this episode.

Mentioned in this episode:

My graphic novel The Devil’s Concubine, which was almost abandoned

My crime noir graphic novel STILETTO finally available in English! Check it out at Thrillbent

Thomas Alsop vol. 1 trade paperback (collects issues 1-4)