A timelipse vid of me “inking” a page of the upcoming book Thomas Alsop from BOOM! Studios.

creativity

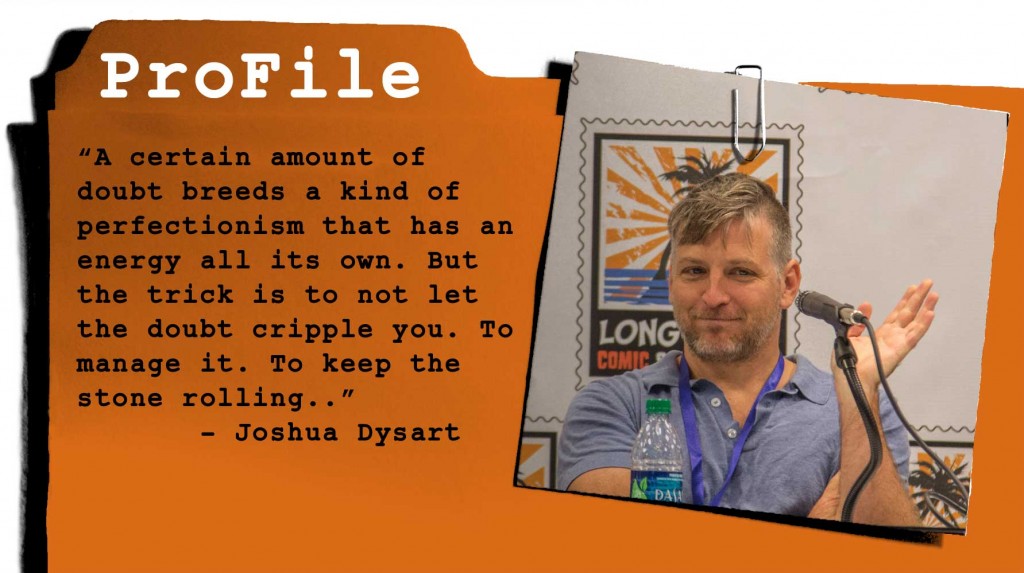

ProFile: Joshua Dysart

Joshua Dysart is a multiple Eisner Award nominated, Glyph award-winning, New York Times Bestselling comic book writer and graphic novelist whose work has been reviewed and discussed by the BBC, CNBC Africa, The New York Times, the Huffington Post and elsewhere. He has collaborated with Mike Mignola, Richard Corben, John Totleben, Igor Kordey, Enrique Breccia, Rick Veitch, Fábio Moon & Gabriel Bá and Eric Powell, among others. He wrote a two year stint of the legendary Swamp Thing and has also worked on Conan, Hellboy and the Hellboy spinoff, B.P.R.D. He’s currently writing the relaunch of Harbinger for Valiant Entertainment and has been called one of the key architects of their universe.

From 2008 to 2010 he wrote a revamp of The Unknown Soldier for Vertigo. The storyline took place in Acholiland, Uganda in 2002 during the war between the Lord’s Resistance Army and the Ugandan People’s Defence Force. Dysart spent a month in Northern Uganda conducting interviews with child soldiers and others affected by the war to research the book.

What made you decide to work in the medium of comics?

It started out as an accident, sort of. I mean, I’ve always loved and read comics. They have always spoken to me. But I never thought of a career in them save for a few attempts at a young age to con artist friends into doing books with me. If I’d been really driven to do it at a young age, I imagine I would’ve also been driven to learn how to draw as well. As it stands my lack of artistic skill is my greatest flaw as a comic book writer. So it was life that made this happen, not me.

I’d done some script supervising work for a very small, struggling movie production company in Los Angeles in my early twenties. The company was run by a friend of mine, Jan Utstien. A few years after I’d stepped down from that gig and gone back to writing for myself (unpublished short stories, poetry, essays, etc.) she phoned me and said that she had fallen in love with a comic book artist. They wanted to self-publish something together but they needed a writer. I wasn’t very enamored with the first pitch they sent my way, so I ended up going to Mexico for a little under a year. Just to knock around down there, check out the Chiapas revolution, go to Guatemala and Belize, that sort of thing. When I got back I was flat broke and really needed something to dig in to. I went back to waiting tables and working in book stores and in my spare time I worked on this comic for Jan and, by then, her husband Bill O’Neal. That book ended up being a black and white self-published book called Violent Messiahs.

This was 1997 and the comics industry was crashing fast. Thousands of stores were closing a year. It was a terrible time to self publish a black and white. But, inversely, the Hollywood gold rush on comics was really starting to escalate. For better or for worse, they saved the comics industry by subsidizing us through that era. Anyway, that very first issue (there was never an issue #2) got passed around LA and I kept flying out from Texas to go to meetings. In 1998 I just figured I should make a go of it. I didn’t really have anything else going on in my life. So I moved to LA and slept on Jan and Bill’s couch and we republish Violent Messiahs in color with a different artist, Tone Rodriguez, at Image. It was here in LA, creating comics everyday all day and being dead, dead broke as I approached thirty, that I started to fall in love with idea of becoming as good as I possibly could at making comics. I spent the next four years sleeping on couches, refusing day jobs (save for the very brief and rare exceptions) living hand-to-mouth and making, mostly shitty, comics every single day. I’ve spent the rest of my life since struggling to understand how to create a great comic. I’ve succeeded a few times, but not as much as I would like.

What part of the process is the most challenging or frustrating to you?

Believing in myself. Writing is a Sisyphean struggle, and Sisyphus knows that you’ve got to get some momentum, some traction on a project, before that stone starts to move. But when you’re at the base of the mountain, only personal faith in yourself will get the stone going. Belief that the ideas will come, that your voice matters, that there’s a reason why you do this awesome job and others don’t, that’s the only thing that’s going to get you started. And you have to find that belief at the start of every single new project. It’s gotten easier over the years for me, of course. Success breeds faith in yourself, but that doubt has never really gone away, and it makes the inception moment of any project extremely difficult. Hell, even just the inception of any single issue comic is pretty hard for me. I would also argue that a certain amount of doubt breeds a kind of perfectionism that has an energy all its own. But the trick is to not let the doubt cripple you. To manage it. To keep the stone rolling. Total faith in yourself will result in unexamined work and halt growth. But total lack of faith will resort in creative paralyses. As with all things, the middle path is the way.

Secondarily, I always have a problem picking my next project. I’m a person that can have a new idea every single day, and that breeds a kind of inactivity. That’s why you don’t see a lot of creator owned stuff from me. If I don’t have an editor to offer me a paycheck and tell me which project they want me to work on, I’ll do a million things at once and none will get done. I’m hoping to learn how to navigate that tendency soon though because I do feel like there’s something missing in my career, and that working on things that belong fully to me might be the missing piece. Of course “Violent Messiahs” was a creator-owned work, but I wrote that over seventeen years ago. I’m a much, much different writer and person now and I look back on that series and wince a little, despite how good it’s been to me all these years.

If you could give one piece of advice to an aspiring comics creator, what would that be?

The best advice I can offer any new comer is that they understand that comics, more than any other medium, is a small community. And you have to become part of that community before you can achieve the goals you have in mind for yourself. You have to make comics and get them out in the world. You have to go to shows. You have to make friends with people in the industry and those at your professional level so that you all lift each other up. You have to invest in yourself. That’s easier than ever now that we have the internet, but it also increasing the amount of noise that’s out there. But that’s okay. Ask yourself, if I never got paid to make comics would I still make them? If the answer is yes, then blaze your trail and make your own work.

Digital vs. drawing on paper

Everything seems to be moving towards going digital – even making comics. But are you ready to make the jump?

While the digital possibilities are vast and very tempting, I still see advantages in the oldschool method of drawing on paper. Here is a list of pros and cons as I see it.

Pros of going digital:

No scanning.

Since you’re drawing your art directly in the computer, there is less hassle scanning and cleaning up your original artwork.

Possibilities

Being able to move and scale ANYTHING, including reference pictures, sketches and word balloons is definetely an upside. With a CINTIQ , you can even draw directly on the pressure sensitive screen (which also turns for maximum line control) and you have everything in one place.

Undo

Am I the only one who sometimes find myself searching for the “undo” button, when I’m drawing on paper? Granted, the so called “lucky accidents” that come from working with a pen or a brush can be a pro as well, but more often than not, you end up with plain old UNlucky accidents – and correcting is a lot easier to do digitally (and with nicer result).

Speed?

It seems for some artists, the possibilities of going digital also offers more speed and momentum to their work. They are simply able to get to a nice result faster. Used efficiently, digital saves you a ton of time.

Cons of going digital:

Speed?

In my experience, any task I take to the computer takes double the time. You can zoom in way too much and nitpick details. You’re working on a device that also has Facebook, Twitter and a gazillion other things running at the same time. I believe “PC” stands for “Procrastination Central”. And the speed of your work depends on the speed of your computer, your software, your file size and all sorts of other fun factors which you have little control over.

Price

You can work digitally with just a computer and a Wacom tablet. But if you really want to go all in, with all the advantages a Cintiq has to offer, get ready to throw almost two thousand dollars on the table. Ouch! You better be sure you can make that money back. Remember though, that equipment you use for your business is usually tax deductable (depending on where you live).

Updates and breakdowns

When has a piece of paper ever asked for an update, or asked for you to plug in the power cord? The reliability on hardware and software is slightly scary (at least for me) because those things can go flaky on you with no warning.

Low mobility

This is a big issue for me. I like being able to sit with a sketchbook or work out of the house for a day. If I had a digital setup, it would most likely be at my studio and too bulky to bring anywhere. However, Wacom has put out a 13.3″ Cintiq that is really lightweight and portable – But you still need to hook it up to a computer to work on it.

Back up

A piece of Bristol board doesn’t suddenly crash on you and leave you to have to reconstruct hours of work. Unless you spill coffee all over your original art, it will usually outlive any computer. And if you scan it in, you have a digital backup as well, a lot safer than having just one file.

No original artwork!

Having drawn it all on the computer, you have no originals to sell at conventions or exhibit at your local library or whatever. Sure, you can make nice printouts, but that’s just not the same, is it? Note that this con could be a pro, since you don’t need storage space for your original art! You can put it all in your Dropbox or on a portable harddisk.

So, what’s the conclusion?

Given the price, low mobility and given the fact that I don’t have the time for the learning curve that going all digital will require (at least before the result is anywhere near what I can produce with pen and paper), I don’t see myself going digital anyt time soon. And I don’t like having to rely on power and technology to be able to make comics.

Creating comics can easily become more than just a hobby, regardless of your preferred drawing method. To find job opportunities for comic book artists, consider exploring platforms like Jooble.

What do you guys think? Are there any pros or cons I missed? And what do YOU use to make comics? Comment below!

Sign up for my FREE 7-day Comics Crash Course

Talent Isn’t Everything – Comics for Beginners podcast episode 22

Are comics for kids?

In my part of the world, comics are often considered something for kids. The colorful, cartoony style often associated with comics is one reason, another is the subject matter and the stories themselves.

In my part of the world, comics are often considered something for kids. The colorful, cartoony style often associated with comics is one reason, another is the subject matter and the stories themselves.

But what about graphic novels such as Persepolis, Jimmy Corrigan or Blankets? That’s not for kids. Yet I often find those books on the shelves of the bookstores next to Naruto and Dragonball, or at the kids literature section at my local library.

In my podcast interview with indie comics creator Jason Little, he talks about his experience with US readers slamming his brightly colored Bee books shut when they realize there’s sex and drug abuse in them. In France it seems they are much more open to adult subject matter being tackled in a cartoony way.

The whole explicit language thing is not something I ever gave much thought in my Danish career, but in the US there are certain words (see? I can’t even write them HERE in fear of getting in trouble!) that will instantly narrow down your reader segment. Some stores won’t even order a book with explicit language! Yet the US comics scene seems to have no trouble with explicit violence! For a foreigner it’s kind of hard to figure out. I can draw a naked breast from the side – a “side boob” (is “boob” a dirty word? I don’t even know!) – but not from the front.

I can understand the want to protect our kids from foul language, but surely foul behavior should be included in this? I can chop someone’s head off in a comic, but I can’t say “shit”.

Oops, just did.

The funny thing about the US scene is that the colorful superhero comics that many associate with kids, are mostly being bought by adults(!). In Denmark, the mantra for many years has been “you want to have a succesful comic book, you have to target kids”. I never bought into this. I always followed my heart in terms of what stories I wanted to tell, then worry about the audience. Slightly naive, I know. But in my mind, comics are NOT for kids. At least not the ones I read – and certainly not the ones I make. And I wish people wouldn’t automatically assume I make stuff for kids, when I say I make comics.

So, I have a question for you: How are comics perceived where YOU’RE from?

Related podcast: Colorful Sex with Jason Little

Sign up for my FREE 7-day Comics Crash Course

ProFile: Kody Chamberlain

Kody Chamberlain spends most of his time creating comic books and graphic novels, but also works in film, animation, video games, and television. Credits include DC Comics, HarperCollins, IDW Publishing, Image Comics, LucasArts, Marvel Comics, MTV, MTV Comics, Mulholland Books, Sony Pictures, 12 Gauge Comics, Universal Pictures, and Warner Bros. In addition to his work in entertainment, Kody also an inspirational keynote speaker and consultant on the subject of creativity. Credits include CTN Animation Expo, HOW Design Live, INNOV8, Modbook, Macworld, iFest, Wizard World Comic Con, as well as AdFed groups and major universities throughout the United States.

You can find out more about Kody at his website: http://kodychamberlain.com.

His latest book SWEETS: A New Orleans Crime Story:

Print edition: http://tinyurl.com/amazonsweets

Digital edition: http://tinyurl.com/digitalsweets

As high school was wrapping up, I had no plan on what to do next. I was interested in a few different things but no real goals so I decided to go to college and figure it out along the way. I thought I might try engineering because I was doing very well in math so I signed up for an advanced math class that was part of the engineering program. I also signed up for a lot of the usual classes you have to take early in college including basic art classes. I was already doodling a bit here and there, so I thought the drawing classes would be fun.

I quickly realized that I hated the math class, and really enjoyed the drawing class. It was a dilemma because I was good at math and bad at drawing. I discovered graphic design somewhere along the way, thinking it might be a nice combination of the two and I picked it as my focus. After a few months in, I started hanging around with a few guys that were serious about comics and that’s what got me hooked.

I was also writing a bit, and thought it’d be fun to try getting into comics. I sucked for a lot of years but I was making slight improvements here and there, and slowly, things got better. I don’t recall ever having a big breakthrough where everything clicked and I made a big jump. I know that happens to artists sometimes, but for me it was a slow grind over many years. I was having a lot of fun and I knew if I kept pushing forward I’d eventually get to a professional level, so I stuck with it.

I started drawing around 1990 or 1991 and started sending out submissions around 1994. In 2002 and 2003 I started to get favorable replies from publishers and editors and I got my first paid work in 2004. Basically, it took me about 15 years of practice to get paid work.

What part of the process is the most challenging or frustrating to you?

The toughest part for me is letting go. I have to constantly remind myself to stop and move on to the next thing. I’ve talked with enough people to know that it’s a very common problem, and I think it’s one of the main reasons many aspiring creators never actually become professionals. I know plenty of people that have been talking about a project for years and claim to have something done on it, but I have yet to actually see anything from it. They’re stuck in the “loop” of reworking material and they never get out. I’m able to work past it, but I’m always a little grumpy when I have to let something go. In reality, if I were to keep reworking it I know I would kill it. Letting go is a daily struggle, but after an issue of a comic hits the shelf, I always feel good about the work. A little distance solves most problems.

If you could give one piece of advice to an aspiring comics creator, what would that be?

Stop sending out scripts, drawing sample pages, and mailing out submissions. Make a comic. You don’t need a team or a publisher, just make it. Write it, create some artwork, letter it, and then put it out. Then do it again. Even if you don’t end up doing every job when you get into the industry, you’ll have a detailed understanding of the process, and that’s an asset. You don’t need permission from anyone to make a comic, and you don’t need much money. The cost of making comics versus film, animation, etc is incredibly low. Once you’ve made a comic you are now a comic book creator, not an aspiring comic creator. You’ll find the industry treats you differently.