Dialogue is usually the only part of the script that makes it to the final comic book. So how do you make it count?

Here are 5 ways to write better dialogue:

Tip No. 1: Ask yourself why.

Why is your character speaking? What is his motivation, the will behind his words. Maybe he wants to show off how much he knows, maybe he wants to insult the other, impress, convince or distract. Maybe he just wants to be left alone. Whatever the will may be, it will affect how the character speaks.

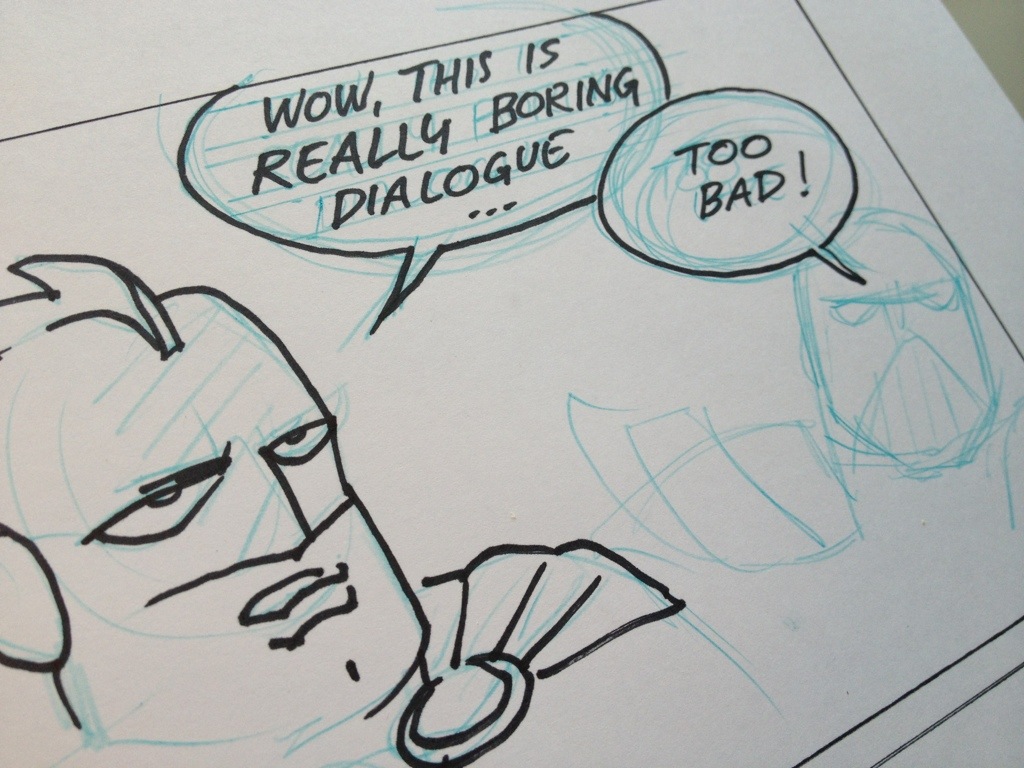

Tip No. 2: Keep it short.

Long, elobarate speeches is for Shakespeare and Bond villains.

Tip No. 3: Let questions go unanswered!

When conversations go “question – answer – question – answer” it feels like treading water. Especially mundane questions like “How was your day?” or “Wonder WHO the killer is?” deserve no answer. Try letting the other character answer with a question – their OWN project, their own will. Like “Did you feed the cat?” or “Where’s my coffee cup?”. Skip the banalities, create conflict instead.

Tip No. 4: The dialogue of the character should reveal character.

The professor and the boxer should NOT sound the same! But for effect, you might twist the klichés once in a while and have the barbarian warrior speak like a philosopher.

Tip No. 5: Variation and rythm.

Remember to vary the length, the tone and the purpose of the word ballons. Just like the panels should have variations in them, the dialogue should keep the readers on their toes, be changing organically. Not the same three-sentence structure in every ballon.

Hope these tips where helpful! If you haven’t already, be sure to join our newsletter and get more free content and tips on how to write and draw comics.

As a scattered artist type, I’m always looking for short simple thoughts the help me wrangle my ideas into place so they don’t get away from me. I can already feel how asking “Why is the character talking?” will allow me to create more depth and asking “does the dialogue reveal character?” will allow me to create more contrast – verbal positive and negative space.

It’s often these little seemingly obvoius tips that make the big difference in how you approach writing. You can read tons of books and then suddenly – something clicks and you finally have the right key. Most of these tips came from my Master Class at the Danish Film School, but I find it directly applicable to almost any form of writing.

Glad you enjoyed the post, Michael, thanks for inspiring me to write it!

Thanks! I’m new to writing dialogues for comics and these tips are very helpful.

Hi,

I’m confused on how to handle characters withholding information from readers for the sake of not spoiling a plot twist. I plan to have a twist villain (X) and only my red herring villain (Y) knows that X is actually a villain prior to the audience reveal. Furthermore, X is aware that Y is the only person who knows that he is a villain.

Since I do plan to have scenes from Y’s perspective, is it unfair to readers that Y is withholding what he knows? I also want scenes from X’s perspective but again, is it unfair to hide what X knows? Or can this be done in the comic medium since we mainly see what characters say and do rather than what they think? Or if I do show what X and Y are thinking in regards to each other, is it possible to avoid them mentioning X’s identity as a villain or is that also cheating the reader since we’re in their head?

Thank you for your time.

Angelo Fresnedi

I got a little confused by the X and Y, but I think any way you can “cheat” the reader is fine by me 🙂 The hero doesn’t have to let the reader know everything, just enough to keep them curious and entertained.

More and more I find that telling an intriguing story is about how you can dish out information. You need to leave breadcrumbs for the reader, enough that they keep on the path and don’t get lost. But not so many that they can see the entire route through the forest and get bored. It’s a delicate balance. Not sure what to tell you other than you need to write it out and let someone read the script, tell you where they figured out who the villain is and where they got confused. I just went through this process with a crime novel and was surprised by a few readers who had missed quite a few of the breadcrumbs I left out. So I left some more and did some recap later in the script so the conclusions made sense.

This is why you need to write a script! Drawing it all out and have readers go “I don’t get it” is no fun.

Hope this is somewhat helpful. Thanks for your comment!